The origins of robust pharmaceutical quality: Contaminated Infusion Fluids

The main content of this blog is only available in English.

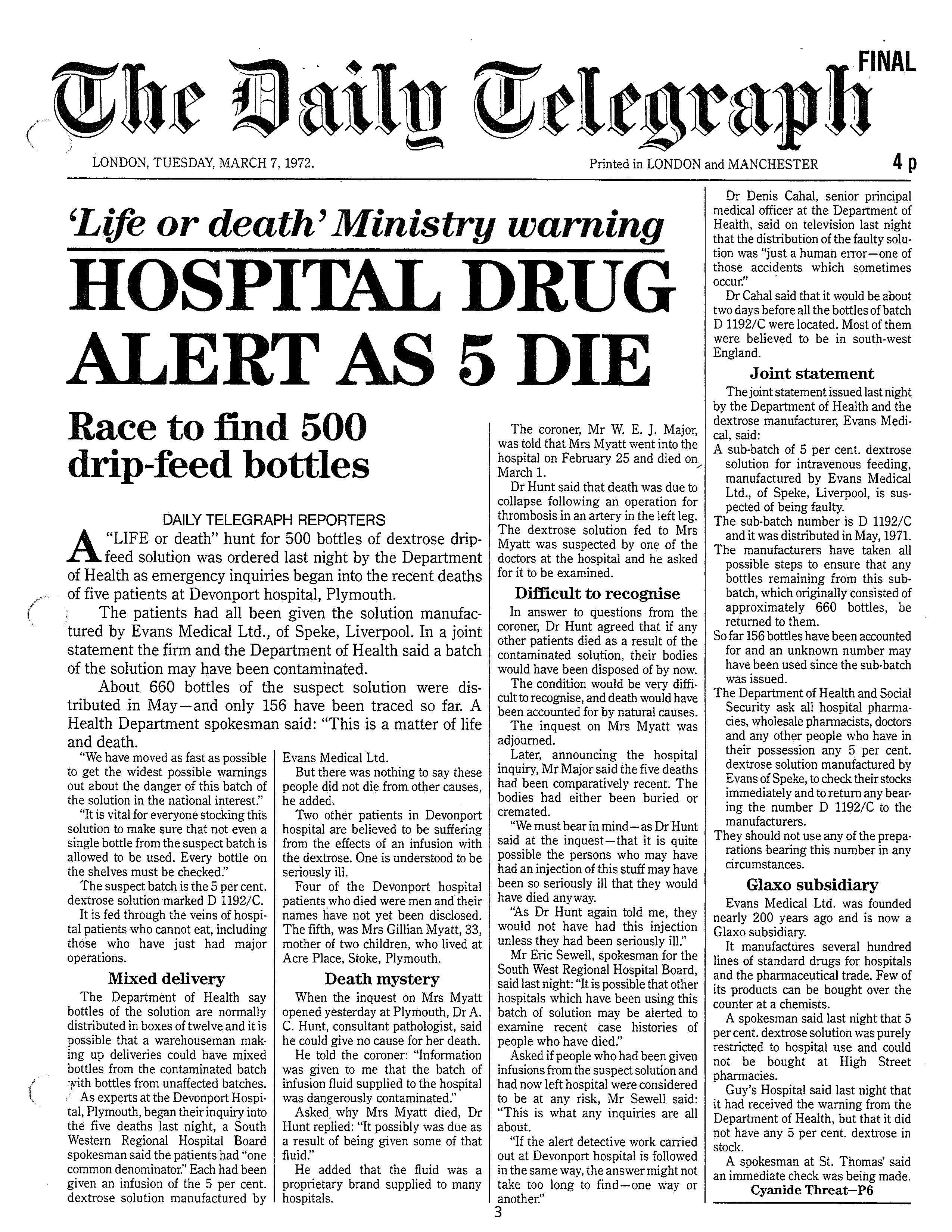

A blog post on the “Clothier Report”. This report was commissionned by the Secretary of State for Social Services of the United Kingdom in March of 1972. The report is named after it’s chairman; C. M. Clothier.

Infusion fluids are sterile solutions in water, intended for injection by slow drip directly into a vein. The production of infusion fluids on an industrial scale is a straightforward process. The prime requirement being the preparation of as clean as possible a fluid.

What happens when this prime requirement is violated is illustrated by the “Clothier Report”. This report was commissionned by the Secretary of State for Social Services of the United Kingdom in March of 1972. The report is named after it’s chairman; C. M. Clothier.

Production of Infusion Fluids

The process

At the time of the incident the method of producing clean (clean in the sense of containing very few bacteria) fluids was well known.The fluids are filled into containers and sterilized by heat. The standard procedure is to maintain the fluid at 115 degrees Celsius for 30 minutes, which is considered sufficient to kill all vegetative forms of bacteria. The process of steriliziation is carried out in an autoclave. Within these autoclaves closed containers of infusion fluid are exposed to steam under pressure. Increased pressure is needed to achieve, with steam, temperatures in excess of 100 degrees Celsius.

The autoclave

To secure satisfactory sterilization autoclaves must be operated so that the contents of all containers in a load are held at the correct temperature for the correct time. The temperature of the steam entering the autoclave can be different from the temperature of the load: the temperature of the load and the time for which it is held are what matters. There is a lag of time between the first admission of steam and the attainment of the correct temperature by the entire load. During this lag, the air is displaced downwards and out of the autoclave. Until this displacement is complete, the resulting air-steam mixture within the autoclave has a lower temperature than that of the steam. Timing of the sterilization period must not begin until the lad period has been completed. The lad period is the period until all air has been displaced and the autoclave contains only steam and the load to be sterilized.

Monitoring the temperature inside the autoclave

To ensure sterilization, the temperature inside the autoclave must be monitored. This was commonly done by observing the temperature of the steam in the autoclave, not the temperature of the load. When this method is used, it is essential for the temperature recorder to show the temperature of the steam in the coolest part of the autoclave. In most autoclaves, this is the condensate drain. This is the location where the temperature recorder sensor should be inserted. Regular checks should be done to verify the relationship between the recorded temperature in the drain and the load temperature. Under perfect conditions the two temperatures will be the same. Any significant differences will indicate a fault.

The Incident

On April 6, 1972 a batch of 5% dextrose influsion fluid (Dextrose Injection BP) was produced in the factory of Evans Medical without adequate steriliziation due to under-processing within an autoclave. As a result, about one third of the bottles contained live bacteria which escaped detection at the factory. Notwithstanding a record of defective processing the batch was released for sale.During the interval between production, sale and use, the remaining bacteria multiplied, producing a dangerous degree of contamination, The batch of contaminated product was distributed to wholesalers, some of it reached the Plymouth General Hospital on 24 February 1972 and 01 March 1972.

The delivery included both sterile and contaminated bottles in the proportion of approximately 2:1. Some of the contaminated bottles were used in the treatment of patients, despite all normal precautions by the hospital staff. As a result of a succession of untoward reactions in patients at the hospital between March 1 and March 3 1972, bottles of the batch came under suspicion and were subjected to bacteriological examination. On the 4th of March, it was confirmed that the bottles were contaminated.

The Contaminated Batch

The contaminated batch in question; D1992/C was produced by the Transfusion Unit at Evans Medical which consisted of two sections;

Solution-making, filling and the autoclaving,

Examination and packaging.

The autoclaving section contained six autoclaves, each fitted with a recording thermometer with it’s sensor located in the condensate drain. Each autoclave is also fitted with a pressure gauge and dial thermometer, both sensing from the top of the autoclave, at -or near- the steam inlet pipe.

The existence of these dial thermometers will later be seen to play a crucial part in the production of batch D1992/C.

Evidence was given to the investigative committee that the dial thermometers were used in an earlier method of operation. They were not intended to be used in connection with process current since about 1966 – the Evans Medical SOP’s on the autoclaving section produced in 1967 make no reference to them.

The method of sterilization employed by Evans Medical follows that described in Production of Infusion Fluids above; the Evans Medical operating instructions for autoclaves are reproduced as an excerpt below this paragraph.

Faulty Temperature Recorders?

Temperature changes

From the evidence of the autoclave operating staff, Mr. Anthony Drummond, an autoclave operator, Mr. Peter Murphy, the chargehand, and Mr. George Sefton, the supervisor, it seems clear that the autoclaving plant had been giving trouble for some time before April 1971. This trouble was evidenced by the temperature recorders either showing a temperature below 240° F (commonly 230° F, or slightly more), or failing to indicate any rise in temperature.

Autoclave 4

The evidence of Mr. Drummond was that the temperature recorder for autoclave number 4 was the most troublesome and that the fault it exhibited was that on occasions it did not record in the sense that the pen did not move from the baseline.On each occasion he reported this to one of his supervisors who would call in either the instrument technician or the engineer. After inspection autoclaving would proceed. Mr. Drummond’s recollection was that generally the recorder would work again after this attention.

Autoclave 6

Mr. Murphy gave evidence that autoclave number 6 had given trouble to the extent that on occasions the temperature recorder indicated temperatures below 240° F, as low as 230° F, at the beginning of a cycle.When this happened the practice was to check that the steam trap was operating and that the pressure was correct, and if they were, to continue the sterilizing cycle.It should be mentioned that Mr. Murphy gave evidence that he was not aware of any occasions on which temperature recorders had shown no rise in temperature above the baseline.

The Committee believes that he was mistaken in his recollection on this point; the evidence of all others in the ‘Iransfusion Unit concerned with the operation of autoclaves was that there were a number of occasions on which the temperature recorder of number 4 autoclave did not indicate any rise in temperature above the baseline.

It must be the temperature recorder

Mr. Sefton gave evidence that from about December 1970 trouble had been experienced with the temperature recorders of autoclaves numbers 4, 5 and 6, on some occasions the recorders showing a slightly low temperature, on others no rise in temperature at all.On these occasions Mr. Coles, the engineer and Mr. Carter, the instrument technician would be called, and on most of the occasions on which he came Mr. Carter would advise that the recorder was broken. Mr. Sefton would then satisfy himself that the autoclave was working properly, by checking that the steam drain and steam trap were working correctly, and continue the sterilizing cycle mainly in reliance on the correct pressure having been achieved.

Replacing the temperature recorders

Mr. Brian Devonport, the manager of the Transfusion Unit, gave evidence that by December 1970 the temperature recorders had given trouble on a number of occasions.About December 1970, after discussion with Mr. Carter, the instrument technician,Mr. Devonport made a late manuscript addition to the capital estimates for the Transfusion Unit for the year 1971 -7 2, in effect requesting the replacement of all six temperature recorders, but for one reason or another this request was not followed up.

Although not being able to offer an explanation of how the practice grew up of operating autoclaves when the temperature recorder was not functioning or at any rate appeared not to be functioning, Mr. Devonport accepted in evidence his responsibility for it.

Improvisation

It should be mentioned here that Mr. Carter ‘s evidence was that he could not recollect any occasion in the period from the autumn of 1970 until he received a request on 6 April 1971 on which he had been called to the Transfusion Unit to look at the recorders.The Committee believes his recollection is at fault on this point, and is satisfied that the temperature recorders appeared to the staff of the Transfusion Unit to need fairly frequent attention.

Certainly the staff came to believe that the recorders were unreliable and for this reason established their own procedure.

The Maintenance Records

Records of maintenance of the autoclaves were produced to the Committee.These showed an initial burst of activity after the overhaul of maintenance records in 196 7, but the system rapidly fell into disuse. By the autumn of 1969 virtually no entries were being made on the records, and as indication of the condition of the plant the records were virtually useless. It should be mentioned here that a check of temperature record charts carried out after this incident of contamination had come to light indicated that on some 70 occasions over the period between May 1970 and September 1971 sub-batches of products had been produced for which the temperature recorder chart showed an inadequate cycle, generally no rise in temperature, or a temperature below the necessary 240 ° F.

It is not now possible to say whether sterilization was inadequate on these occasions but it seems probable that this was the case for at least some of the sub-batches.From the Committee’s point of view in relation to its terms of reference, the importance of these records is that they confirm that an unauthorized procedure for operating autoclaves had become established.

The processing of sub-batch D 1192C

On 6 April 1971 a batch of 5% dextrose infusion fluid numbered D1192, just over 4 ,000 bottles in all, was processed in the autoclaves of the Transfusion Unit.As was the custom, the batch was divided into six sub-batches and each given a suffix A to F according to the autoclave in which it was to be processed. The order of starting up the autoclaves was 6, 5, 4 etc., and sub-batch C 6 was placed in autoclave number 4.

The number of bottles constituting the sub-batch was 612; these were loaded into two cages, each of which had three levels.

On this day both the supervisor of the solution-making, filling and autoclaving section of the Transfusion Unit, Mr. Sefton, and the chargehand, Mr. Murphy, were absent for different reasons. Thus Mr. Devonport, the departmental manager, was singlehanded so far as supervision of the work of this section was concerned, including the operation of the autoclaves. The autoclave operator at work on this day was Mr. Drummond.

Mr. Drummond’s evidence was that on this day he started the sequence of operations necessary on autoclave number 4, but found that after the admission of steam to the autoclave had begun, the temperature recorder did not indicate the expected rise in temperature.Vial of the contaminated batch: Dextrose Injection BP of sub batch D1192/C

Yet another recorder failure?

Mr. Drummond reported this to Mr. Devonport, and it seems clear that both assumed that this was another instance of recorder failure.

With hindsight it is possible to say that there is a probability amounting almost to a certainty that the recorder was functioning and correctly indicating no rise in temperature in the condensate drain. However, autoclaving was continued according to the procedure which had become established in reliance on the dial thermometer indicating a temperature of 240° F., and the pressure gauge indicating a pressure of 10 lb. per square inch above atmospheric pressure, ignoring the recorder indication.

At the public hearings Counsel for Evans Medical made the point that the operating instructions laid down by Evans Medical for autoclaving had not been followed. In particular it was said that, if the instructions had been followed, processing could not have been continued, since they called for the marking of the temperature trace for the beginning of the cycle at the point where it reached 240° F.

However, other evidence given to the Committee indicated that the operating staff had found two other instructions -number 8 and number 9 -needed interpretation to produce a satisfactory result.

The positioning of the pressure gauge was such that following instruction number 8 could lead to the introduction of air to the autoclave because it indicated a positive pressure ( above atmospheric) when a partial vacuum still existed. Thus it became the practice to shut off the steam at intervals and then read the pressure before continuing steaming, if necessary, to ensure that there was a slight positive pressure before opening the condensate drain valve.So far as instruction number 9 is concerned, evidence was given that it was necessary to close the condensate drain valve when the temperature had reached about 220° F., otherwise the autoclave would not reach the required 240° F.

The operating staff therefore knew that in two respects the operating instructions could not be regarded as mandatory. So far as the use of the temperature recorder was concerned, the staff had available a dial thermometer which had been observed to indicate the same temperature as the recording themometer when all was functioning correctly.In fact Mr. Drummond said in evidence that he had been told to use the dial thermometer in the event of the recorder not working. It is true that the operating instructions did not say that this dial thermometer could be used; it is also true that the instructions did not say that the dial thermometer must not be used. The Committee finds it difficult to criticize the operating staff for using the dial thermometer in their endeavours to continue production, when there was no clear instruction to the contrary.

Production continues

Processing of sub-batch D1192C therefore continued making use of the dial thermometer and pressure gauge, and so far as could be recalled by the staff concerned all proceeded normally.In reality all was far from right; it was later shown that of the bottles recovered from sub-batch D1192C approximately one third were contaminated and on this evidence could be assumed not to have been sterilized.

The remainder were sterile.Various theories were advanced as to how this came about, for example, that air could have been admitted in error during the processing, or that water could have been present to a considerable depth in the bottom of the autoclave.

But the only theory fully consistent with the established facts was that a layer of air was present in the bottom of the autoclave surrounding the lowest of the three layers of bottles, thermally insula